Going Into Detail

For a place named “Earth,” the oceans appear wildly over-represented. I haven’t been able to make more dirt, so I’ve been working on the representation angle a bit lately:

This representation isn’t “to scale” in the Cartesian sense, though maybe it’s to scale emotionally. I’m adjusting levels until they’re within the range of human feeling. It’s a theme-park, Le Petit Prince, Mario Galaxy kind of feeling, a cartoon.

And though manipulated, the source data is real, taken from NASA scans. In a way, I’m changing the apparent physical properties of the globe’s material, from the unmediated, authoritative pixel-as-data — each point claiming a one-to-one correlation with some kind of empirical measurement — to something more recognizable, more like a plastic vac-u-form raised-relief map.

At this level, you can recognize the borders of some countries, which immediately suggests one point: much of history is dictated by topographical features — oceans, rivers, and mountains, especially — which aid or hinder our collective ability to move around and bump into each other.

The western end of Eurasia is called Europe. (“Europe” might mean, more or less, “the western end.”) It’s particularly history-dense; people have been bumping into each other here for a long time, in part because of the nature of its topography.

We think of it as a distinct place because as places go, it’s comparatively hard to enter and leave — to the north, west, and south, it’s bordered by water; to the east, by a long history of disagreements, primarily over where the border lies.

Mapmakers have long attempted to use various geographical features to define Europe’s eastern border for their own purposes, citing rivers, mountains, and so on. These days, the Urals are most often given as the boundary; this is partly because they happen to be the unusually well-preserved result of two sub-continents running into each other, and this carries a lot of weight with people who base arguments on precedent. But it’s also because it allows Moscow to be European without defining all of Russia as part of Europe, the prospect of which irritates cartographers.

The truth is that to the east, there is no easy physical border, only a cultural gradient, built in great, shuddering spasms by the Persians, Greeks, and Romans, the Schisms, and the Wars, marked in literal form by walls and metaphorical form by curtains. It’s messy, but that’s hard to draw on a map.

Some astronauts have described a phenomenon called the overview effect whereby, when viewed from space, the Earth’s distinct lack of visible political borders reveals the ultimately unified character of human civilization. I get the feeling this may also just describe the kind of relief you get from vacation, an escape from the effort required to internalize so many of the arbitrary facets of human civilization simultaneously.

Of course, if we all lived in orbit, I expect we’d find other ways to separate ourselves. At any rate: time for a segue.

One boundary that’s never been in question is the Alps. (“Alps” more or less means “mountains.”)

Inconveniently located in prime central Europe, the Alps have formed the northern physical and conceptual border of Italy since before the Romans.

For instance, in the middle ages, when a non-Italian man was elected to the papacy, he was described as papa ultramontano: the pope from over the mountains. Later, the phrase swung 180 degrees, again hinging on the Alps: French Protestants described supporters of papal authority as Ultramontaignes, referring this time to Italy.

And of course there’s Hannibal. Nobody’s sure where he and his pachydermatic procession perambulated across the Alps. We only have the stories, and some of them conflict. But few doubt that he crossed — the fact of the mountains remains.

Mountains are good at forming boundaries. Nobody knows this better than the Swiss.

Switzerland is serious about their heightmaps. Two-thirds of the country is Alps. This is one of the reasons they’ve been neutral for so long: invading them thoroughly is a huge pain. Panzers, especially, aren’t so good on an incline.

The Swiss capitalized on this, building a series of fortifications called the National Redoubt to which their army could retreat if threatened, which says something about their national character. These days, they’re leasing bunkers as data storage, and debating shuttering the system, which says something else.

At any rate: by now they’ve scanned their country at extremely high resolution. You can buy the entire dataset, the whole country, for about $125,000.

I think that’s fascinating. The Swiss will sell you a comprehensive, intimate knowledge of their country’s topography for an eighth of a million dollars. If nothing else, this shows how confident they are in their borders.

I did not buy the Swiss data. The mountains seen above are still based on the NASA heightmap. But at this level I’m using color data from a different source, processed through an open-source tool which removes the clouds from satellite imagery. So it’s still “free” data, but getting it required some work.

This part of Switzerland, centered around a prominent valley, is known as Valais. (“Valais” more or less means “valley.”) At this level we’re running into the limits of the publicly-available color data, but the NASA height data still holds up — the Valais is clearly visible.

This is one of the more stereotypically Swiss parts of Switzerland, and not only for topographic reasons: Valais was the last rebel state in the Sonderbund to surrender. To understand this sentence, you must know es bitzeli about Swiss politics.

As a political structure, Switzerland somewhat resembles the original United States: proudly independent regions united by convenience, with a long tradition of mutual confederacy. Its unification as an official nation-state was a reluctant, somewhat stuffy affair, spurred only by periodic realizations that cooperation was marginally less tedious than invasion.

The last major internal conflict was partly Rome’s fault, again. The rural Swiss states (and by “rural” read “mountainous”) were predominantly Catholic — Ultramontanes, to be specific — and the prospect of increasing unification with the Protestant states put a papal bee up their butt. So they created an alliance rather double-speakily named the Sonderbund (the “separate league,” or “sunder-band,” more or less) and attempted to secede.

A stately general named Defour led the campaign that changed their minds, claiming fewer than a hundred deaths, most of which were accidental. He ordered his troops to spare the injured, the victory led to the modern Swiss Republic, and the general later helped form the Red Cross.

How Swiss! The most civil war ever. Even across a Schism, the Swiss states had a kind of internal cultural cohesion peculiar to the region. Having lived my entire life either in a network of remote valleys or online, I can attest to the feeling of surly camaraderie which exists when introverts of a similar stripe are forced together by circumstance. Geological and technological barriers become naturalized as cultural barriers, and eventually you’re all drinking together and comparing scars.

Speaking of which:

So, that was an ugly transition. This zoom level is where the free data breaks down. What licensable data exists is browsable with Google Earth, though not easily extractable, and is of course laden with restrictions.

This scan of the Matterhorn was made recently by a flock of new-fangled lidar-drones, and published on GitHub by the drones’ marketing team. And instead of a heightmap (which, as an image file, could theoretically contain useful metadata, including latitude and longitude) they released a free-floating “point cloud,” a set of 3D coordinates that are only situated in reference to each other, plus a texture stitched together from a bunch of photos. To create and position the above model, I had to convert the pointcloud to a heightmap through a series of complicated steps which I can’t recommend, and won’t describe, and then I had to guess the georeferencing points by squinting at satellite imagery. The point is: data with no context is just numbers. But back to the mountain.

The Matterhorn is terrifying. It was one of the last great Alpine peaks to be climbed, mainly because it’s so scary-looking. In person it appears scale-free, just the wrong size, distorting distances around it as it towers over the meadows below. (“Matterhorn” more or less means “meadow mountain” in German.) (In Italian it’s known as Monte Cervino, which more or less means “forest mountain,” which suggests they named it before the Swiss burned down the forest and made a meadow.) (“Swiss” might mean “burners.” Apparently they cleared some forests in their day. Okay, I’ll stop.)

It’s probably the most famous Alp that I know of. Walt Disney once had a copy made with a basketball court in the peak. The real one is on the border between Switzerland and Italy, and has two peaks, one on either side of the border; the Italian peak is slightly shorter.

It was first summited by an Englishman named Edward Whymper; his rival, an Italian, was 200 meters from the summit when he saw Whymper waving at him from above. The Italian turned around and went back down.

I’ll now stop paraphrasing Wikipedia and quote it directly, as it quotes from a book describing the mountain: “Stronger minds,” remarked Edward Whymper, “felt the influence of the wonderful form, and men who ordinarily spoke or wrote like rational beings, when they came under its power seemed to quit their senses, and ranted and rhapsodised, losing for a time all common forms of speech.”

Given that, I won’t say much else about the Matterhorn, except to point out that it’s a very clear boundary. It feels like a place where one ought to stop, turn around, and go back.

I suppose that’s the benefit of using physical features as borders: they’re indisputable. Maybe national borders are a map of where people got tired of arguing over where the borders are. I suppose without the physical boundaries, it’s harder to tell where one’s obligations start and end, which brings us back out to space:

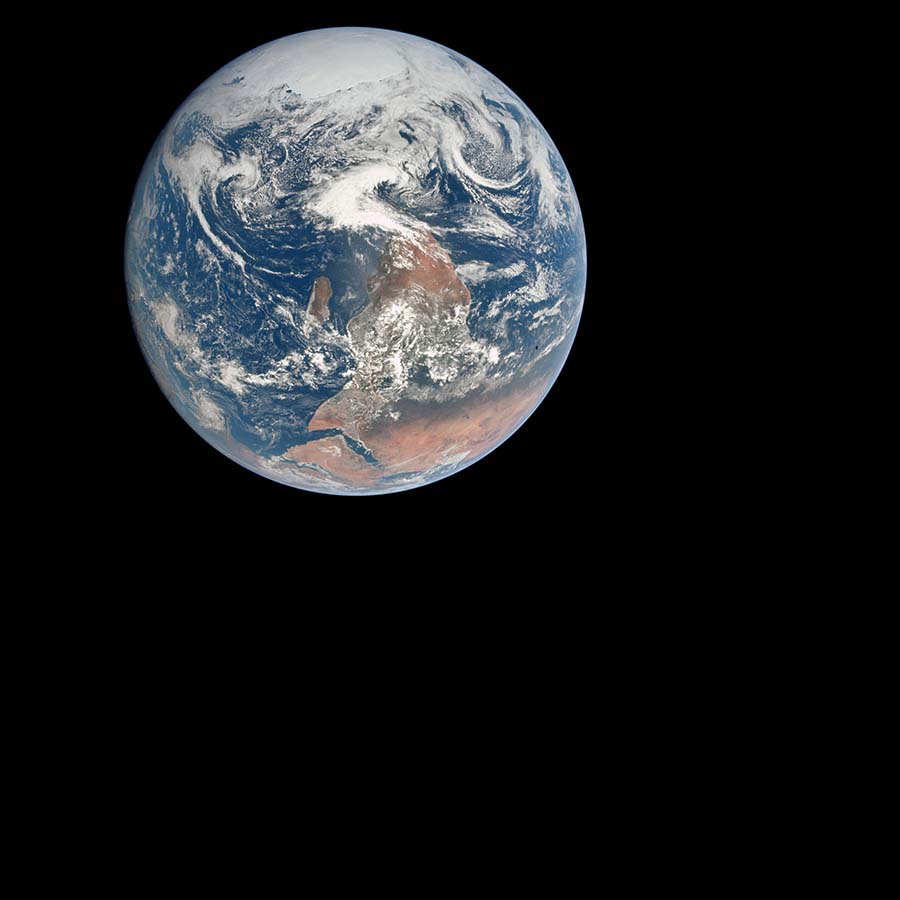

The 1972 photo of Earth known as “The Blue Marble” is now ubiquitous, a cliché, shorthand for “everything that matters,” but without going into specifics. But as summaries go, the photo is weirdly editorial: we see clouds, and sea, and a lot of Africa. No mountains are visible, hardly any forests, certainly no cities. Nothing of any scale that we can apprehend directly. It’s strikingly humanity-free.

In this way, the photo makes a kind of political statement — a “truth claim” — which is both vague and hyperbolic simultaneously. This is the context, it says. This is the whole thing. But of course that’s ridiculous. It is obfuscatory in its apparent completeness. It’s a map of the planet’s color and brightness, at relatively low resolution. It is a context — we get to decide for what.

History is made of stories. And to be clear: I mean stories that we tell ourselves, and that wouldn’t exist otherwise. They’re a mental hack we use to order and interpret the available data, more self-consciously now than ever. The grand determinist narratives of the past are now rightly seen as embarrassing artifacts of a pubescent culture.

But our age will be seen that way too. The entire history of History has been the gradual overthrow, reinterpretation, and assimilation of old stories by new ones. We have to have these stories. They’re how we know things. The fact that they are almost certainly not “true” in the sense we imagine shouldn’t mean they’re useless. I’d just prefer to be more self-aware about what we think we know, what we’re making up, and where the border between those things lies.

I mean: even the mountains are moving. The tip of the Matterhorn is from something that became Africa, and will eventually be something else. None of these things exist as distinct, concrete “things” except with our active involvement. And of course, as has been implicit since the adoption of a long-range view of Earth as an environmentalist symbol: If we blow it, the Earth won’t miss us. Borders are drawn and redrawn for our convenience. The mountains will continue to move underneath them.

I like to imagine this relates to what Stewart Brand was getting at with his “We are as gods” minifesto in the first Whole Earth Catalog. It’s a bit mind-numbing to see our actions observably affecting the whole planet at once. Even when you accept the fact, it still feels unreal.

It’s hard enough to understand how we behave locally, much less on a planetary scale, and even less how all the different scales relate. I want better, more visible ways of setting and viewing context, ways which reveal the underlying assumptions and manipulations and allow for adjustments.

So that’s why I made this demo.

Explore an interactive version of this demo on github!

And here’s a link to the repo.

More than anything, this is a proof of concept; a sketch of an idea. It conjures up a number of related ideas, like rendered tilesets of public-domain heightmap and satellite imagery, and perhaps an interface like the one suggested above for navigating, layering, and displaying them.

Further, and with thanks:

- Jen Lowe on memory, and context, and empathy: The Entropy of Memory

- Charlie Loyd on facts, interpretation, and empathy: Making Smart

- Charlie Loyd on the Earth as a context: Politicizing Sandy